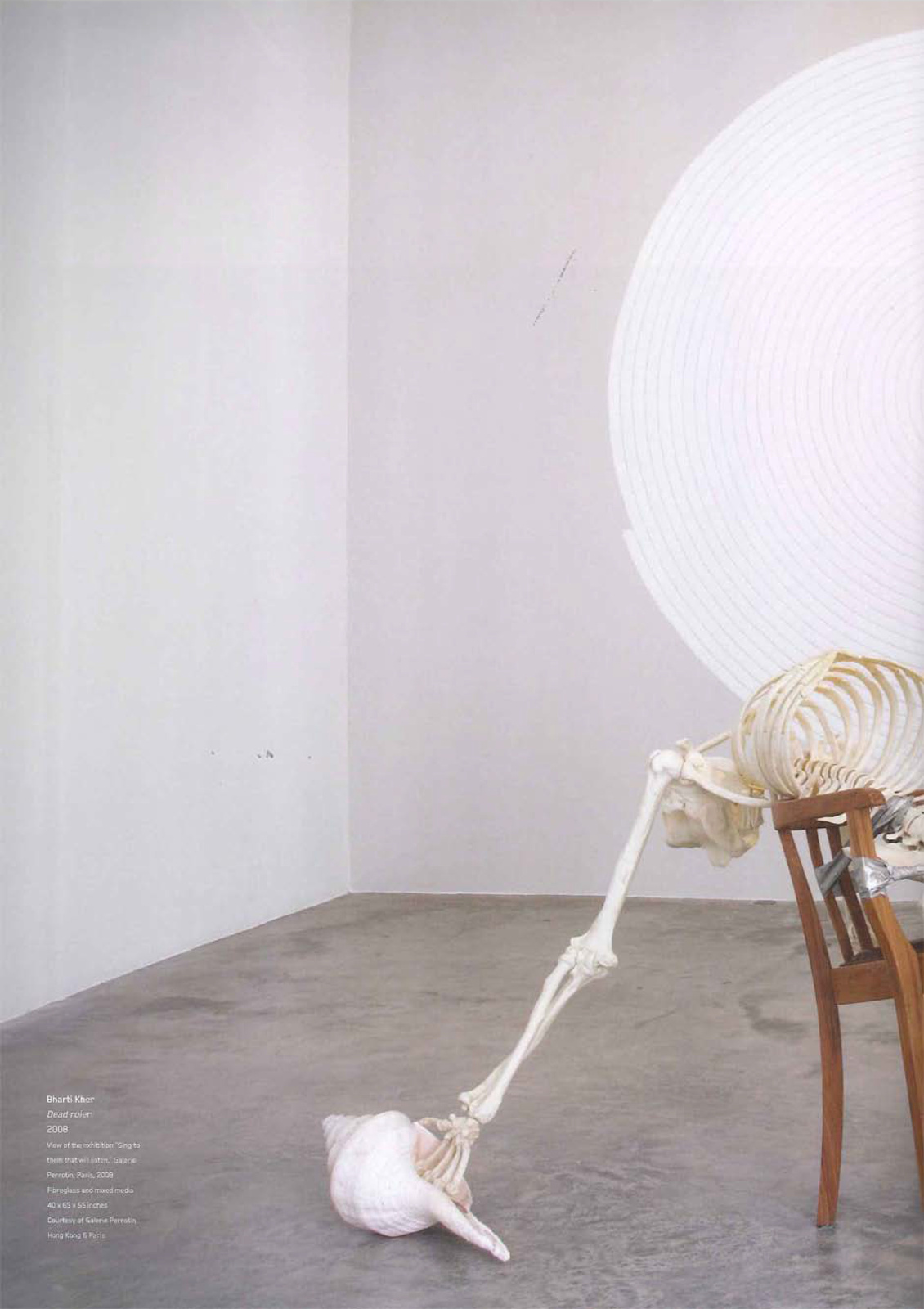

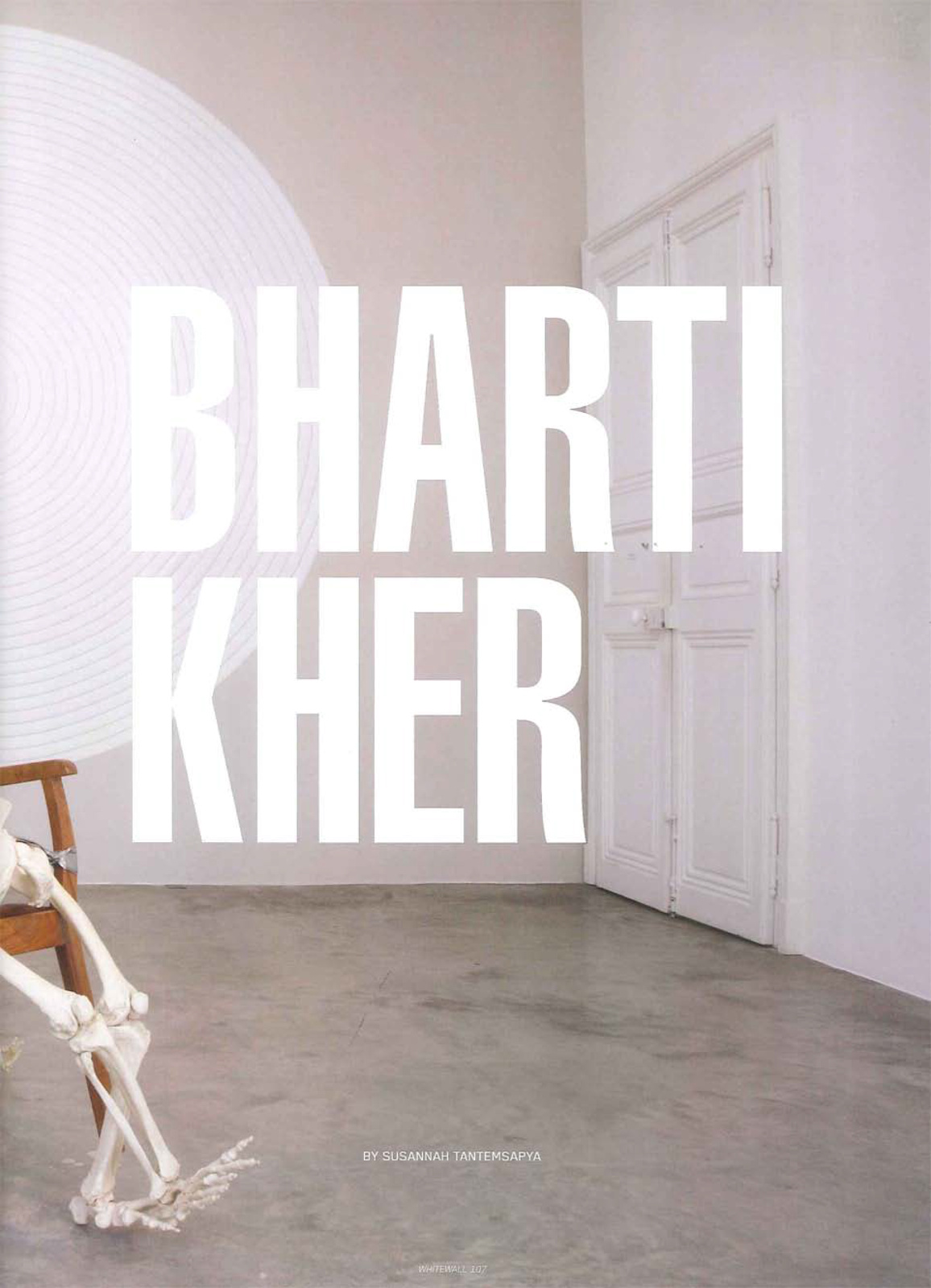

Bharti Kher

by Susannah Tantemsapya

Whitewall Magazine - The Design Issue (Summer 2013)

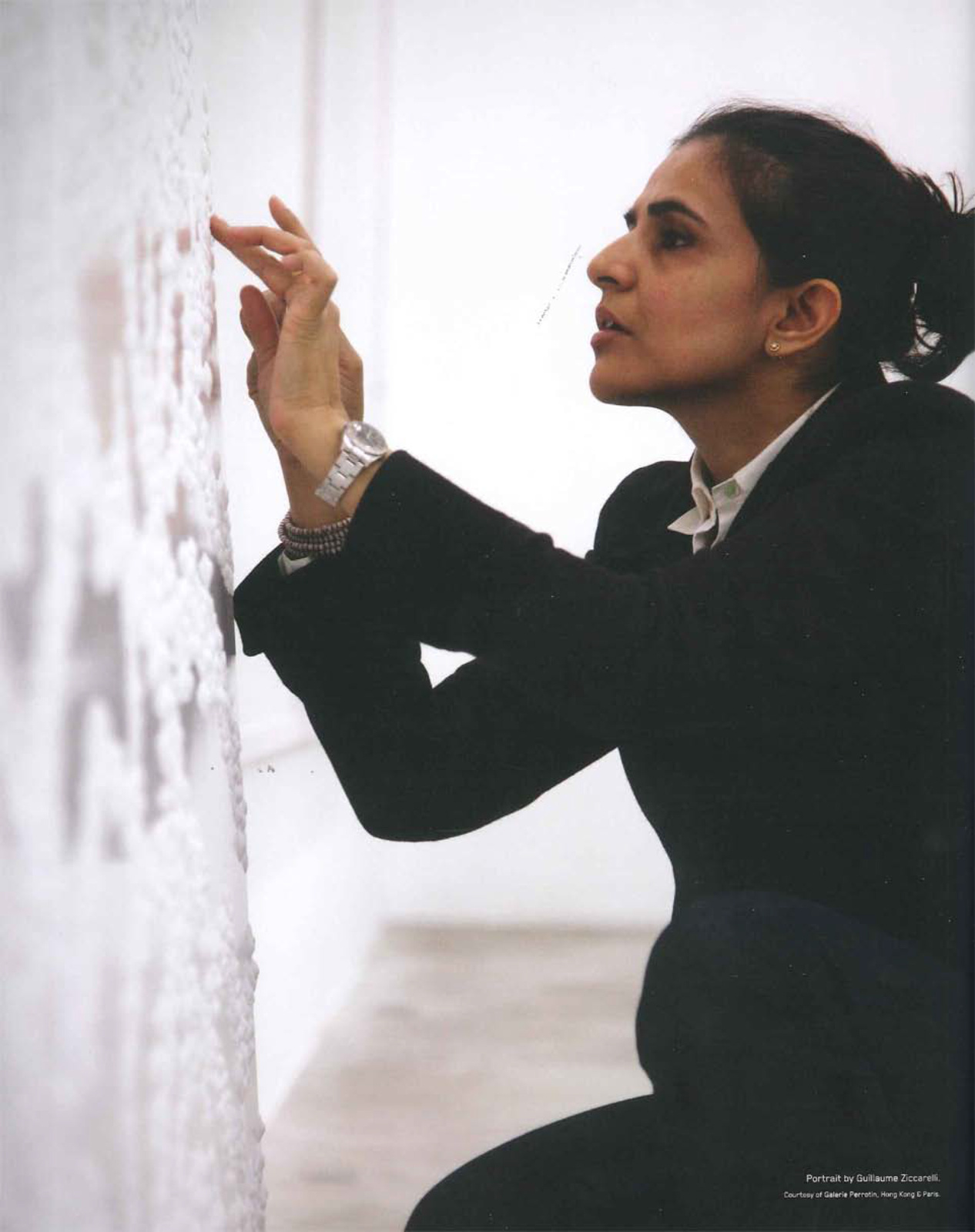

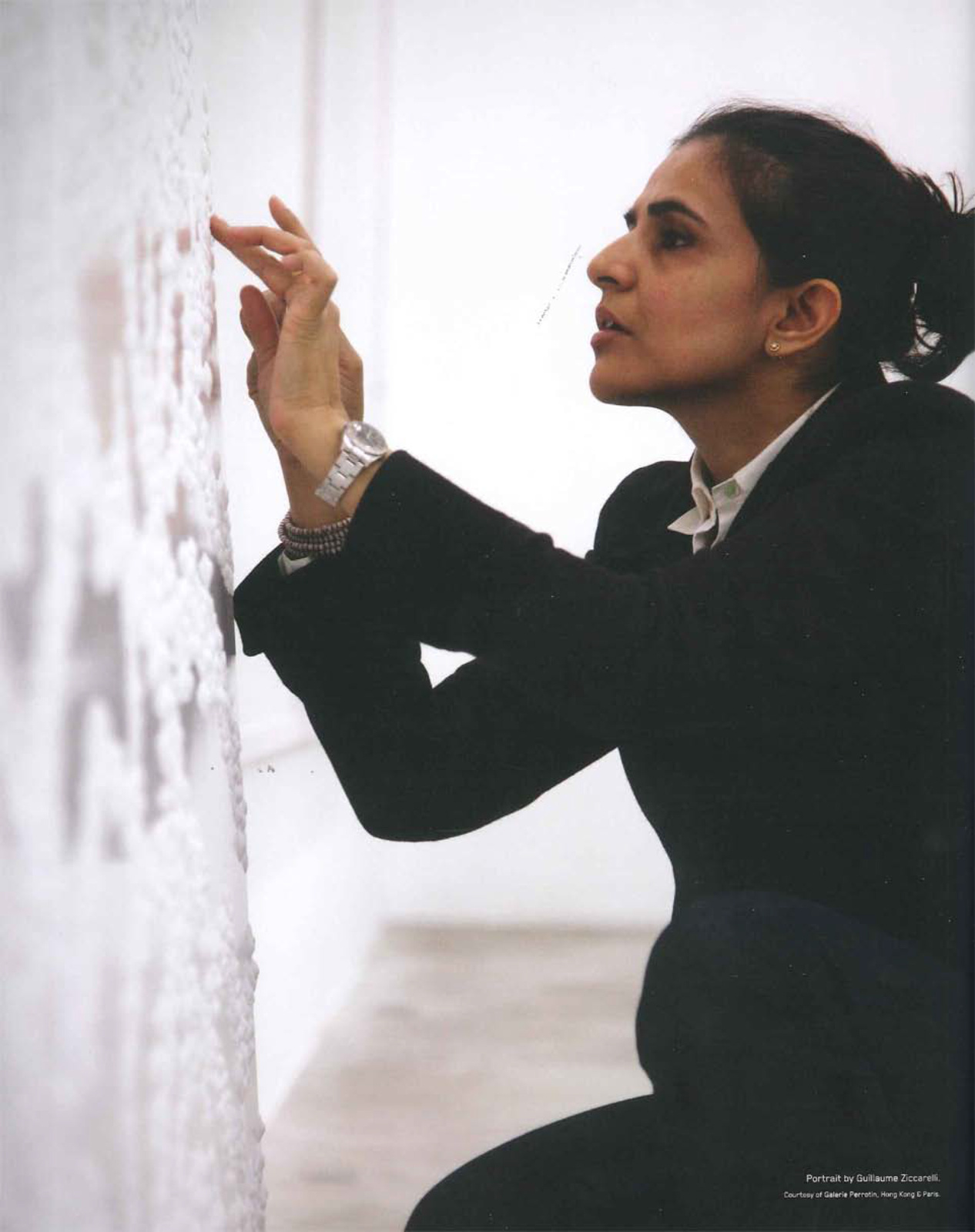

Bharti Kher is an unstoppable force in the Asian art world. Born in 1969, she grew up in the suburbs of London after he parents emigrated from India. After graduating art school, she traveled to New Delhi in 1993, having flipped a coin to decide between there and New York. Two weeks later, she met her now-husband, artist Subodh Gupta. She has been living there ever since. In 2006,Kher gained international recognition with her life-sized elephant sculpture covered in gray bindis entitled The skin speaks a language not its own. Coming off of four major shows in 2012, Kher reflects her work, its place in the world, and why she dislikes the word “diaspora.”

WHITEWALL: Bindis, as well as saris, appear consistently throughout your work. You grew up being surrounded with these objects in your mother’s fabric shop in London. How has your relationship to these materials evolved since childhood?

Bharti Kher:

When I started working with bindis, I wasn't remembering my childhood at that specific moment. My parents are from the rag trade. When I hear the sound of fabric being cut, when I smell fabric, it reminds me of my mom's shop.

When I started working with bindis, I wasn't remembering my childhood at that specific moment. My parents are from the rag trade. When I hear the sound of fabric being cut, when I smell fabric, it reminds me of my mom's shop.

The felt of the bindis is this completely opaque fabric that absorbs light. A good crepe silk has a heaviness, a parachute silk has a lightness, so fabrics also create and reflect light. These are kind of formal things that work when you put them in a bigger scale. They start to work in a very subtle way, so perhaps there are things that people don't notice specifically, but it's something I was extremely aware of.

I collected saris for a long time. There's something extremely performative about wearing a sari: that you wrap it around your body, that you do the pleats, that you throw over your shoulder, you check the length. The body becomes like gesture. When I was hardening and stiffening the fabrics, it was actually quite nice, the idea of the continuation of readymade, which is something I had already done with the bindis. I was intrigued that nobody else had really used this material before. Here it was in front of you all the time. You can turn the idea of the cliché on its head and do other things. The sari pieces now are almost portraits. Like totems, like women that I have met, they're people I know.

WW: How do various women, particularly in India, respond to these elements?

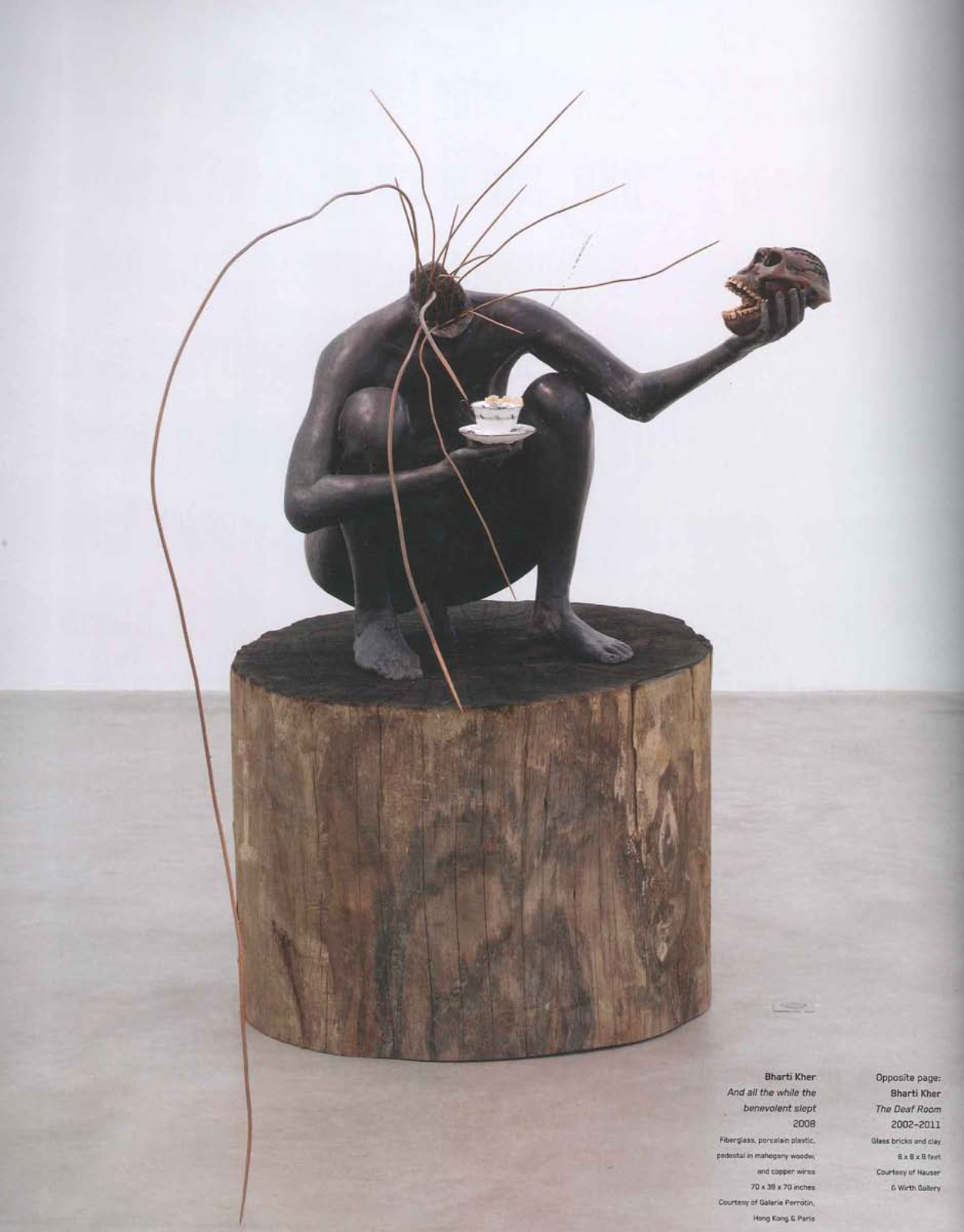

BK: My practice is quite wide, so people respond to different types of work in different ways. Women sculptures are stronger, more goddesslike. The responses are really positive, even though it's sometimes little macabre or slightly violent. Women respond quite well to my work. In terms of the bindi work, all types of people respond on many different levels. Some are idols that lead people to other places. Some people respond to the idea of the language in the work, the idea that they could be codes or letters or text. Then some respond to purely visual.

WW: What role does color play in your work?

BK: I love color. I'm a colorist. Color is a massively important part. I spend a lot of time thinking about it and exactly what's that going to do to a particular work and how it's going to influence the direction of the piece. I think about color all the time.

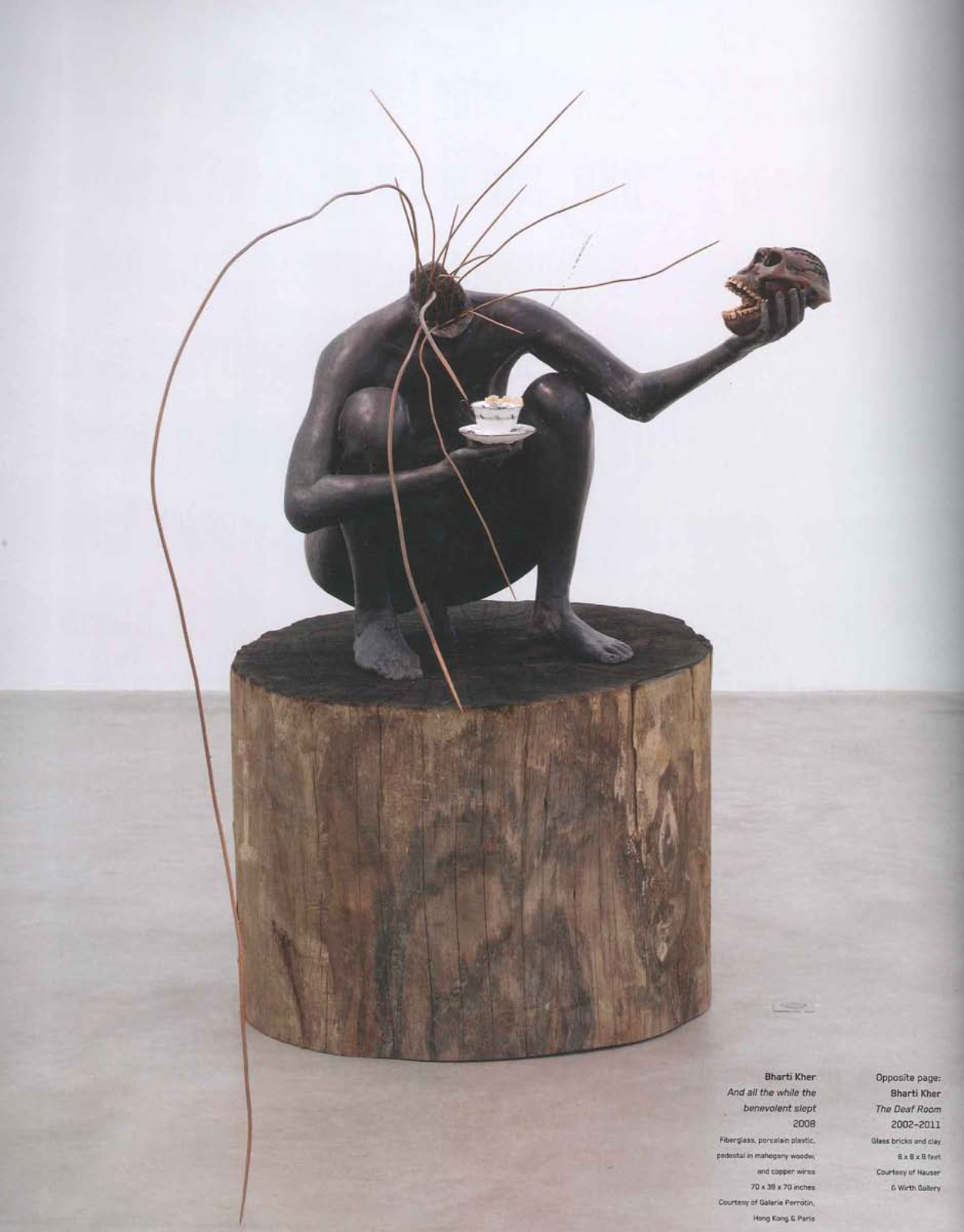

WW: Your work tackles the repression and continual shift of women’s roles in Indian society, as well as blending traditional mythology. How do these elements interrelate to one another? Is there a specific ancient story that resonates to this theme?

BK:

There isn't a particular story. The role of the goddess is important in Indian mythology and religion, part of the collective conscience, the idea of the female as the protector and giver, the creator, the destroyer. Kali is one of the goddesses I find extraordinarily intriguing because she is a kind of hybrid. She sometimes can be perceived as masculine because she's the fighter, the destroyer, the incarnate of evil. I'm intrigued by contradiction. I like the idea of the constant questioning of roles models.

I want to make a series of women goddesses over a period of 10 to 12 years that one day I can show all together. The idea of the goddess has been somehow subdued or silenced in a way because people are afraid of the idea of very powerful creation. Who are the old Celtic goddesses? Who are the old Viking goddesses? Who are the Asian goddesses? Where are they from? How do they reincarnate themselves? How have they been silenced? How have they been subdued?

When I made The messenger [2011], the goddess is the sky walker. It's this idea that she can be anywhere. She has this strong sexual energy that's very unashamed and unabashed. At the same time, she walks the clouds. That's where she stays. She refused to stay down amongst us. She doesn't want to be specifically categorized. Only 100 years ago in Europe, if you were too outspoken, you could have been sent to a mental asylum. We forget – time is very short.

How do you look at the half-empty glass of water? It's a common analogy. How do you look at these images? This past year has been really interesting in terms of how women are taking hold of a public space, how they are creating their own voices after the gang rape case of last year.

WW: Why do you dislike the word “diaspora”?

BK: I don't want to be known as a "diaspora" artist. Find another name for me – I'm not interested in that one.

![]()

BK: I don't want to be known as a "diaspora" artist. Find another name for me – I'm not interested in that one.

Why categorize? I'm a practicing artist who works. Where I come from, what I do, where I live... I think those ideas are a little bit dated now. It's limiting. Maybe in the sixties, seventies, even the early eighties, it was something that described a group of people, but I'm not interested in being a part of a band. The reason that you become an artist is that you find your own way.

My work, in some ways, is very contradictory. I set it up for one thing; you think you know what it is, and then you don't. I don’t want to be pinned down. There's not one right answer about who I am. There's not one right answer for what my work is.

My work, in some ways, is very contradictory. I set it up for one thing; you think you know what it is, and then you don't. I don’t want to be pinned down. There's not one right answer about who I am. There's not one right answer for what my work is.

WW: What has been the reaction to your work in India versus overseas? Do you have more recognition overseas or in your own country?

BK: My first breaks were overseas. People were watching me in India in a smaller way. The biggest breaks I got were outside of India. Then, of course, those have repercussions when you're back home. I don’t think one should underestimate the audiences in any country. People take with them their own baggage when they walk into a space. I mean all the good things and all the bad things. It's like they carry a suitcase of knowledge with them, which is part of their physiognomy – it's like part of their brain.

Certainly, more people see my work outside of India than they do in India. Ten thousand people will see my show in London. Maybe less than 800 will see my show in Delhi. It's also about awareness. Those are much broader issues that will sort of take the whole day to discuss and unpack. The art world in India is very small: Delhi, Bombay, and Bangalore, maybe Calcutta. Everybody still knows each other.

WW: How has that changed in the 20 years that you have been in India?

BK: It was absolutely miniscule, and now it's larger. There are more players and galleries. We had a biennale this year, which was great. There's a lot more international interest in India. More people come to visit to see. They're interested in the history and the artists. There are a lot of great artists in India. Their works are original, interesting, they've had a prolonged career of continuous practice. It's surprising when new people and faces come into it already, growing in the art world. There's room for more.

India's at a massive turning point, so the next 20 years will be very important: politically, economically, just the way society will perhaps change. It's a country in flux. It's a very interesting time. There's a lot of anxiety as well as hope, excitement as well as pessimism. The political class has not been able to bring in the kind of change that people want to see. These things take time. I think people should look at culture as part of the package, the way they view their country and history, look at the museums and use public spaces to own the city, to be part of a space. Those things are not developed at all yet.

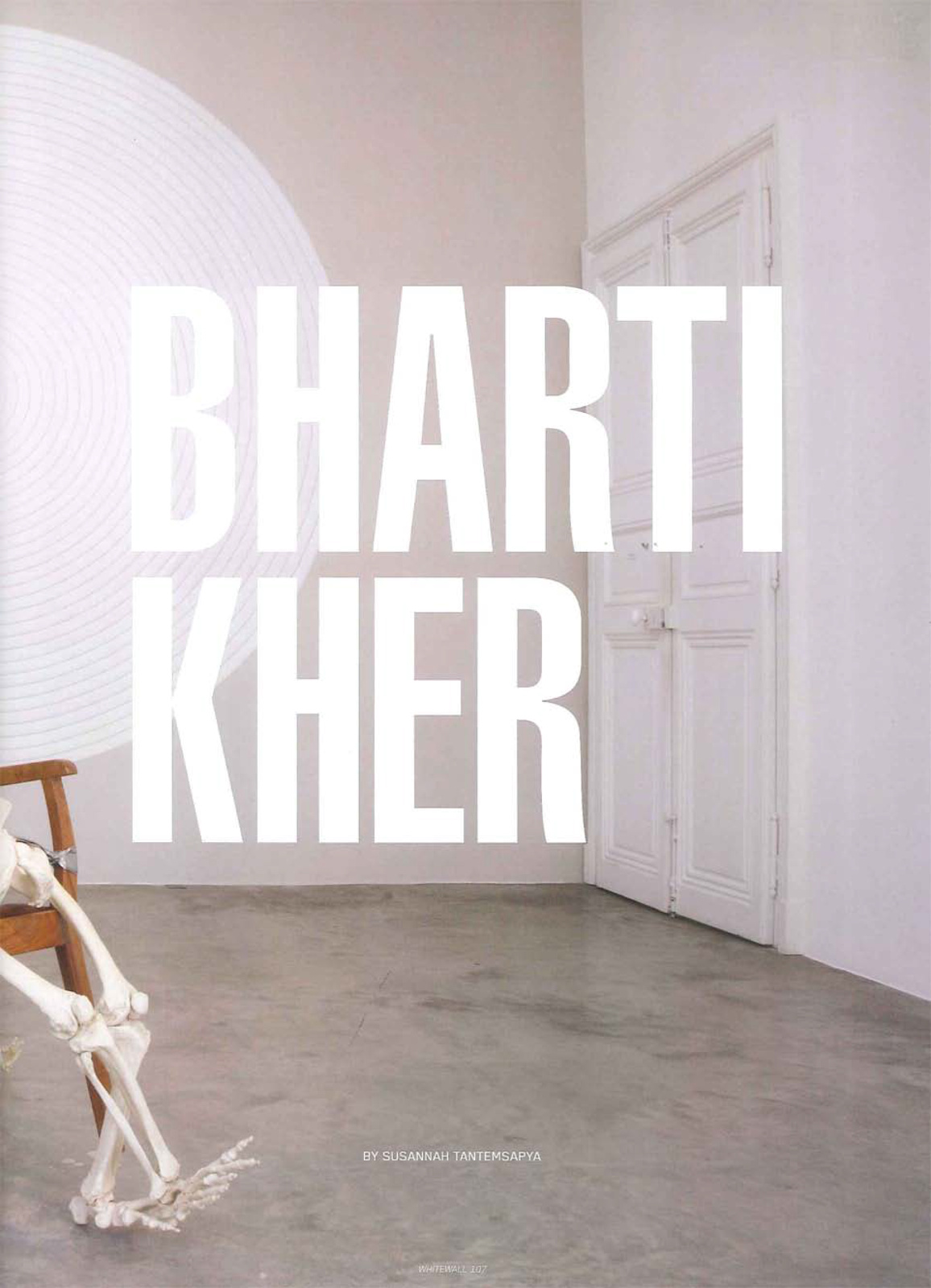

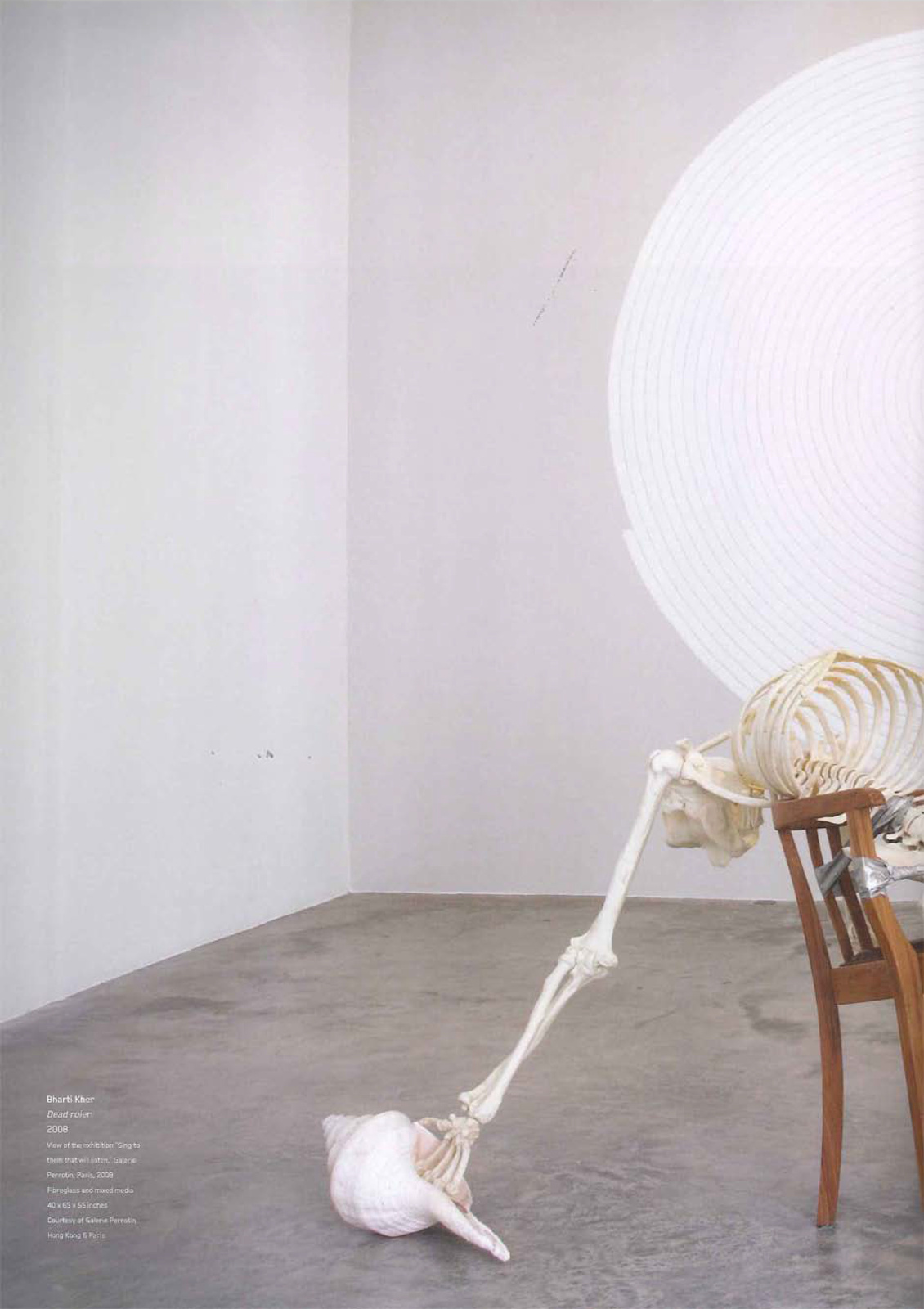

WW: Can we discuss the large-scale installation pieces shown at Galerie Perrotin? These a bigger, heavier, and void of the color you are known for.

BK:

I made these pieces over a period of about 15 years. The deaf room [2012] is probably the earliest one. It is made from red bangles that have been melted down into brick forms. It's something that I made in the early 2000s and those have been in my studio for years, as well as the radiators for maybe eight years. Eventually, all these works were formed strangely. I just decided that now is the time for those to be out there.

I see these as a trilogy. These all talk about the phantasm of the home. The deaf room is really about silence, the disenfranchised people, the women who are no longer there. The confession room, Confess [2010], is the dialogue with the self. In a matriarchal society, this would be her bridal chamber. If you look inside, it's full of bindis and has lots of color.

I made these pieces over a period of about 15 years. The deaf room [2012] is probably the earliest one. It is made from red bangles that have been melted down into brick forms. It's something that I made in the early 2000s and those have been in my studio for years, as well as the radiators for maybe eight years. Eventually, all these works were formed strangely. I just decided that now is the time for those to be out there.

I see these as a trilogy. These all talk about the phantasm of the home. The deaf room is really about silence, the disenfranchised people, the women who are no longer there. The confession room, Confess [2010], is the dialogue with the self. In a matriarchal society, this would be her bridal chamber. If you look inside, it's full of bindis and has lots of color.

The hot winds that blow from the West [2011] is about talking. The radiators being a formal folly, the idea that you create this space of warmth and a kind of safety in a way. Actually, these are defunct now; you kind of get the feeling of heat, but they're cold. They are like strange animals that have been stacked together. The title comes from the idea that when you live in India, the summers come; there's the hot wind that blows in from the deserts in Rajasthan across the city. It dries you to the bone. You have to experience that heat to really understand what it is. It's so hot. At the same time, the idea of the radiators, I sought them in America and then sent them back to America, almost like a warning.

There's this sea of mumerings, chatter and whispers coming from the other side of the world that affect Asia, India in specific. It's also the idea of playing with the language. What's this idea of hot winds? It's sort of a load of rubbish coming from there. When you send this work back, it's sort of like sending a warning that times are changing. The idea of the winds always bringing change, the eye of the storm has a unique knowledge. I suppose it's a dialogue, really; it sort of goes around, moves in and out like that.

WW: What's next for you?

BK: The next six months will be introspection, thinking. I've got a couple of places where I'm going to be traveling, just to read and think. Last year, I had a very busy year. It was extremely productive. I made a lot of work. Now I've got to really just sit and think about what I did. I have two shows, both in Asia, and a few group shows here and there.

Now, restart, replenish, reorganize the studio, get the materials ready for the next big body of work. I had four solo shows last year – that was a crazy but good year. Now, I'm going to keep it quiet.

- Print -