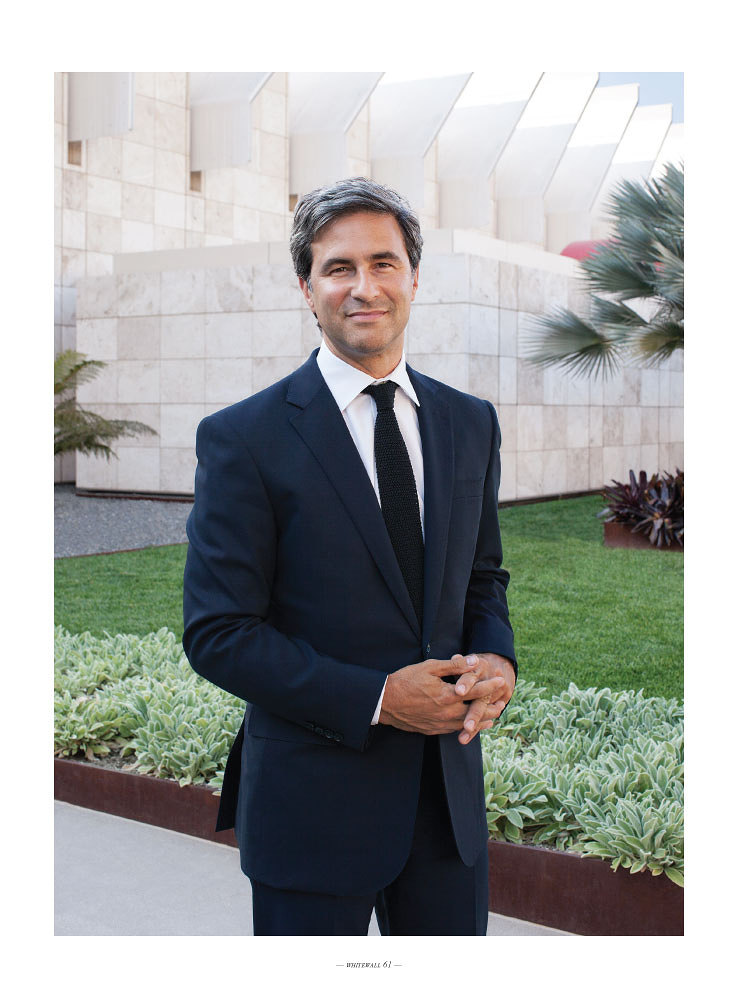

Michael Govan

by Susannah Tantemsapya

Portrait by Claudia Lucia

Whitewall Magazine - The Luxury Issue

(Winter 2012/13)

Los Angeles is slowly becoming a central force in the art world, and Michael Govan is leading the way. In 2006 he left the Dia Foundation in New York to become the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Since then, he has integrated art, nature, and architecture on its campus by acquiring permanent installations such as Chris Burden’s Urban Light, Robert Irwin’s Palm Gardens, Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Shafted), and Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass (over the back parking lot). With recent retrospectives focusing on the work of Ed Ruscha and Stanley Kubrick, this institution is combining art and film in an unprecedented fashion. Whitewall sat down with Govan to learn more about where LACMA is headed, and why Los Angeles is the city of the future.

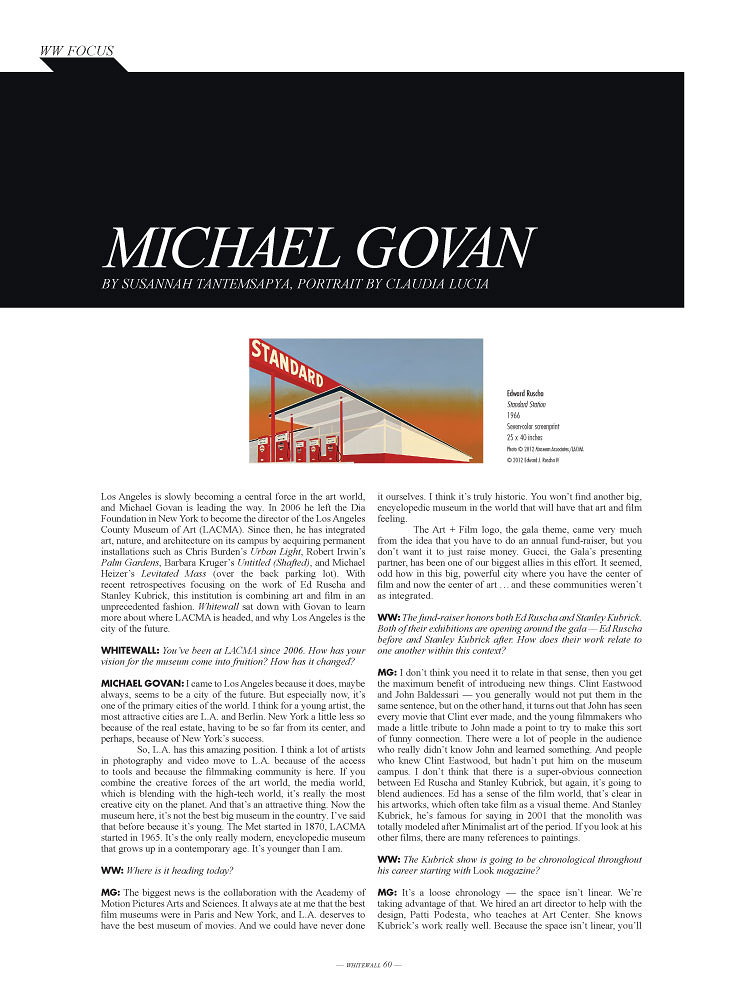

Edward Ruscha

Standard Station, 1966

Image Credits: The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

WHITEWALL: You’ve been at LACMA since 2006. How has your vision for the museum come into fruition? How has it changed?

Michael Govan: I came to Los Angeles because it does, maybe always, seems to be a city of the future. But especially now, it’s one of the primary cities of the world. I think for a young artist, the most attractive cities are L.A. and Berlin. New York a little less so because of the real estate, having to be so far from its center, and perhaps, because of New York’s success.

So, L.A. has this amazing position. I think a lot of artists in photography and video move to L.A. because of the access to tools and because the filmmaking community is here. If you combine the creative forces of the art world, the media world, which is blending with the high-tech world, it’s really the most creative city on the planet. And that’s an attractive thing. Now the museum here, it’s not the best big museum in the country. I’ve said that before because it’s young. The Met started in 1870, LACMA started in 1965. It’s the only really modern, encyclopedic museum that grows up in a contemporary age. It’s younger than I am.

So, L.A. has this amazing position. I think a lot of artists in photography and video move to L.A. because of the access to tools and because the filmmaking community is here. If you combine the creative forces of the art world, the media world, which is blending with the high-tech world, it’s really the most creative city on the planet. And that’s an attractive thing. Now the museum here, it’s not the best big museum in the country. I’ve said that before because it’s young. The Met started in 1870, LACMA started in 1965. It’s the only really modern, encyclopedic museum that grows up in a contemporary age. It’s younger than I am.

WW: Where is it heading today?

WW: The fund-raiser honors both Ed Ruscha and Stanley Kubrick. Both of their exhibitions are opening around the gala — Ed Ruscha before and Stanley Kubrick after. How does their work relate to one another within this context?

MG: I don’t think you need it to relate in that sense, then you get the maximum benefit of introducing new things. Clint Eastwood and John Baldessari — you generally would not put them in the same sentence, but on the other hand, it turns out that John has seen every movie that Clint ever made, and the young filmmakers who made a little tribute to John made a point to try to make this sort of funny connection. There were a lot of people in the audience who really didn’t know John and learned something. And people who knew Clint Eastwood, but hadn’t put him on the museum campus. I don’t think that there is a super-obvious connection between Ed Ruscha and Stanley Kubrick, but again, it’s going to blend audiences. Ed has a sense of the film world, that’s clear in his artworks, which often take film as a visual theme. And Stanley Kubrick, he’s famous for saying in 2001 that the monolith was totally modeled after Minimalist art of the period. If you look at his other films, there are many references to paintings.

MG: The biggest news is the collaboration with the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. It always ate at me that the best film museums were in Paris and New York, and L.A. deserves to have the best museum of movies. And we could have never done it ourselves. I think it’s truly historic. You won’t find another big, encyclopedic museum in the world that will have that art and film feeling.

The Art + Film logo, the gala theme, came very much from the idea that you have to do an annual fund-raiser, but you don’t want it to just raise money. Gucci, the Gala’s presenting partner, has been one of our biggest allies in this effort. It seemed, odd how in this big, powerful city where you have the center of film and now the center of art . . . and these communities weren’t as integrated.

WW: The fund-raiser honors both Ed Ruscha and Stanley Kubrick. Both of their exhibitions are opening around the gala — Ed Ruscha before and Stanley Kubrick after. How does their work relate to one another within this context?

MG: I don’t think you need it to relate in that sense, then you get the maximum benefit of introducing new things. Clint Eastwood and John Baldessari — you generally would not put them in the same sentence, but on the other hand, it turns out that John has seen every movie that Clint ever made, and the young filmmakers who made a little tribute to John made a point to try to make this sort of funny connection. There were a lot of people in the audience who really didn’t know John and learned something. And people who knew Clint Eastwood, but hadn’t put him on the museum campus. I don’t think that there is a super-obvious connection between Ed Ruscha and Stanley Kubrick, but again, it’s going to blend audiences. Ed has a sense of the film world, that’s clear in his artworks, which often take film as a visual theme. And Stanley Kubrick, he’s famous for saying in 2001 that the monolith was totally modeled after Minimalist art of the period. If you look at his other films, there are many references to paintings.

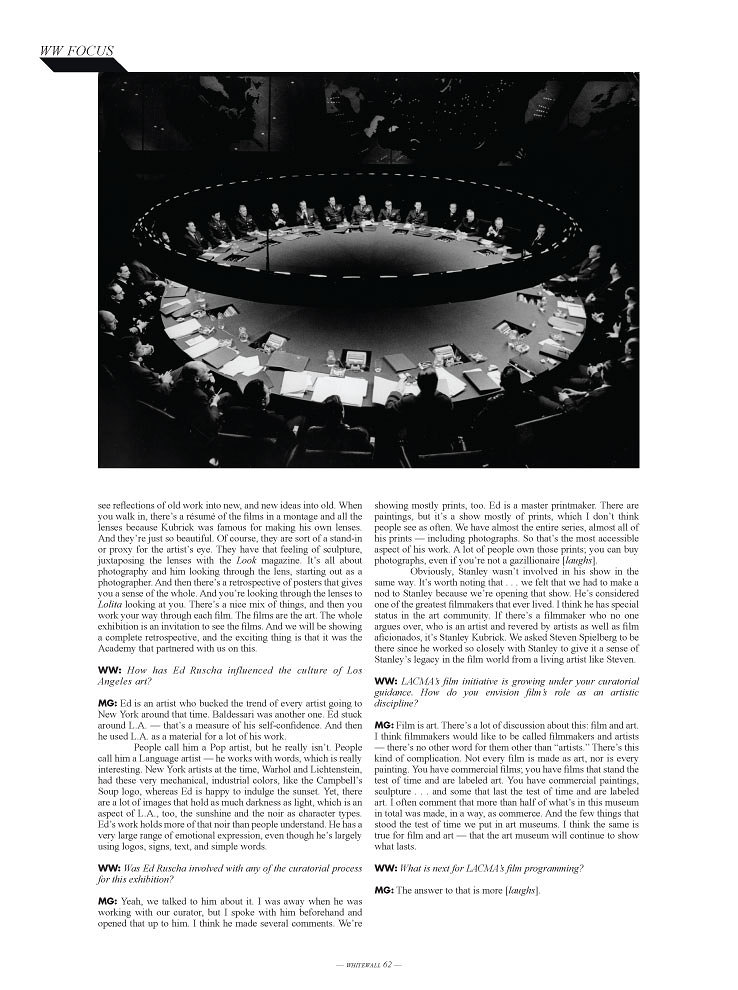

Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb Directed by Stanley Kubrick (1963-64; GB/United States)

The Conference table in the War Room. ©Sony Pictures Inc.

WW: Was Ed Ruscha involved with any of the curatorial process for this exhibition?

MG: Yeah, we talked to him about it. I was away when he was working with our curator, but I spoke with him beforehand and opened that up to him. I think he made several comments. We’re showing mostly prints, too. Ed is a master printmaker. There are paintings, but it’s a show mostly of prints, which I don’t think people see as often. We have almost the entire series, almost all of his prints — including photographs. So that’s the most accessible aspect of his work. A lot of people own those prints; you can buy photographs, even if you’re not a gazillionaire [laughs].

Obviously, Stanley wasn’t involved in his show in the same way. It’s worth noting that . . . we felt that we had to make a nod to Stanley because we’re opening that show. He’s considered one of the greatest filmmakers that ever lived. I think he has special status in the art community. If there’s a filmmaker who no one argues over, who is an artist and revered by artists as well as film aficionados, it’s Stanley Kubrick. We asked Steven Spielberg to be there since he worked so closely with Stanley to give it a sense of Stanley’s legacy in the film world from a living artist like Steven.

The ShiningDirected by Stanley Kubrick

(1980, GB/United States)

The daughters of former caretaker Grady (Lisa and Louise Burns)

©Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

The ShiningDirected by Stanley Kubrick

(1980, GB/United States)

The daughters of former caretaker Grady (Lisa and Louise Burns)

©Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Directed by Stanley Kubrick (1965-1968)

The astronaut Bowman in the storage loft of the computer HAL

©Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

2001: A Space Odyssey

Directed by Stanley Kubrick (1965-1968)

The astronaut Bowman in the storage loft of the computer HAL

©Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. WW: LACMA’s film initiative is growing under your curatorial guidance. How do you envision film’s role as an artistic discipline?

MG: Film is art. There’s a lot of discussion about this: film and art. I think filmmakers would like to be called filmmakers and artists — there’s no other word for them other than “artists.” There’s this kind of complication. Not every film is made as art, nor is every painting. You have commercial films; you have films that stand the test of time and are labeled art. You have commercial paintings, sculpture . . . and some that last the test of time and are labeled art. I often comment that more than half of what’s in this museum in total was made, in a way, as commerce. And the few things that stood the test of time we put in art museums. I think the same is true for film and art — that the art museum will continue to show what lasts.

WW: What is next for LACMA’s film programming?

MG: The answer to that is more [laughs].

MG: Film is art. There’s a lot of discussion about this: film and art. I think filmmakers would like to be called filmmakers and artists — there’s no other word for them other than “artists.” There’s this kind of complication. Not every film is made as art, nor is every painting. You have commercial films; you have films that stand the test of time and are labeled art. You have commercial paintings, sculpture . . . and some that last the test of time and are labeled art. I often comment that more than half of what’s in this museum in total was made, in a way, as commerce. And the few things that stood the test of time we put in art museums. I think the same is true for film and art — that the art museum will continue to show what lasts.

WW: What is next for LACMA’s film programming?

MG: The answer to that is more [laughs].

- Print -