Shepard Fairey

by Susannah Tantemsapya

Whitewall Magazine - The Design Issue

(Summer 2011)

Shepard Fairey has evolved from being the underground artist who

created the “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” phenomenon to making

work that propels social change on a massive scale. His foray into

mainstream America happened when his iconic image of Barack

Obama became synonymous with the 2008 presidential election.

Spanning two decades, Fairey’s career has existed both inside

and outside of the predominant system without compromising his

ideals. For example, look at his recent propaganda-style image for

Green Patriot Posters, a project that uses dynamic graphic design

to educate the public about global climate change. Fairey is the real

deal. He constantly challenges himself to grow as an artist, and is

passionate about his work’s style and subject matter.

Shepard Fairey

Sunsets to Die For, 2007 Mixed-media painting on canvas

Courtesy of artist

WHITEWALL: How has the role of your work evolved from “questioning authority” to now taking specific stands on issues?

SHEPARD FAIREY: When I was younger, I felt that people were

too willing to fall submissively in line, but I didn’t think telling

people how to think or behave got great results. My approach

was to make imagery that called things into question and allowed

people to come to their own conclusion. With all the forces

out there manipulating people for their [own] ends, I needed to

be more outspoken about specific issues. Honestly, my earlier

hesitation wasn’t that I didn’t have my own opinions, but maybe

I was scared about getting the flack from someone saying,

“I disagree.” I’ve become a little bit more courageous, and also just recognize the necessity.

There’s a danger of becoming didactic the same way some oppressive forces are. I really try to be as careful about that.

Propaganda has always had a sinister connotation. I don’t think that

it’s sinister in nature. I think that people who want to manipulate

it for their own ends are the ones that utilize it most frequently. If

there were activists creating positive counterpropaganda, it could

actually affect the culture around it in a very positive way.

WW: How do you see the relationship of art and social change expanding?

SF: My hope is that art can do what other media can’t do. Media will not penetrate people who are predisposed to resisting it. If it doesn’t align to their point of view, they will shut it out without reading through an article, without watching a video, et cetera. Art, on the other hand, has the ability to entice people, capture their imagination — and they let their guard down. I’m not saying that all art is able to do that, but the best art is able to do that. It functions in a completely different way. It’s about how it makes you feel. You want to intellectualize that feeling. That is incredibly powerful. It only works when it’s coming from a pure place. When people see street art done by corporations as a marketing campaign, they intuitively recognize it as bullshit. It would be great if more art had social messages, but it needs to come from an honest place.

WW: I just read about this OK Soda campaign (created by

The Coca-Cola Company) in the early nineties from a ‘SuP

MAGAzIne interview you did about 12 years ago.

SF: I did a campaign to sabotage it in Boston [laughs]. I made

“AG” (Andre the Giant), instead of “OK.” It was illustrated with

Andre’s face with the same sort of grunge haircut and all that

stuff. I took all their slogans, which were sort of very Marshall

McLuhan–esque, like “The more OK you consume, the more OK

you feel.” I changed them around, and made them more obviously

manipulative.

That was the first time in my adult life that I really recognized this underground culture of punk rock, comics, and grunge all getting to a place of commercial liability where a big corporation is going to jump on that look. It totally offended me then. I’m used to that now. now if I saw that, I’d say I’m better off continuing with my images about human rights in Burma or for the Peace Corps or to expose

the insidious influence of the Koch brothers. I’m less likely to protest it now than to just say if you want to do something powerful, it has to be authentic.

That was the first time in my adult life that I really recognized this underground culture of punk rock, comics, and grunge all getting to a place of commercial liability where a big corporation is going to jump on that look. It totally offended me then. I’m used to that now. now if I saw that, I’d say I’m better off continuing with my images about human rights in Burma or for the Peace Corps or to expose

the insidious influence of the Koch brothers. I’m less likely to protest it now than to just say if you want to do something powerful, it has to be authentic.

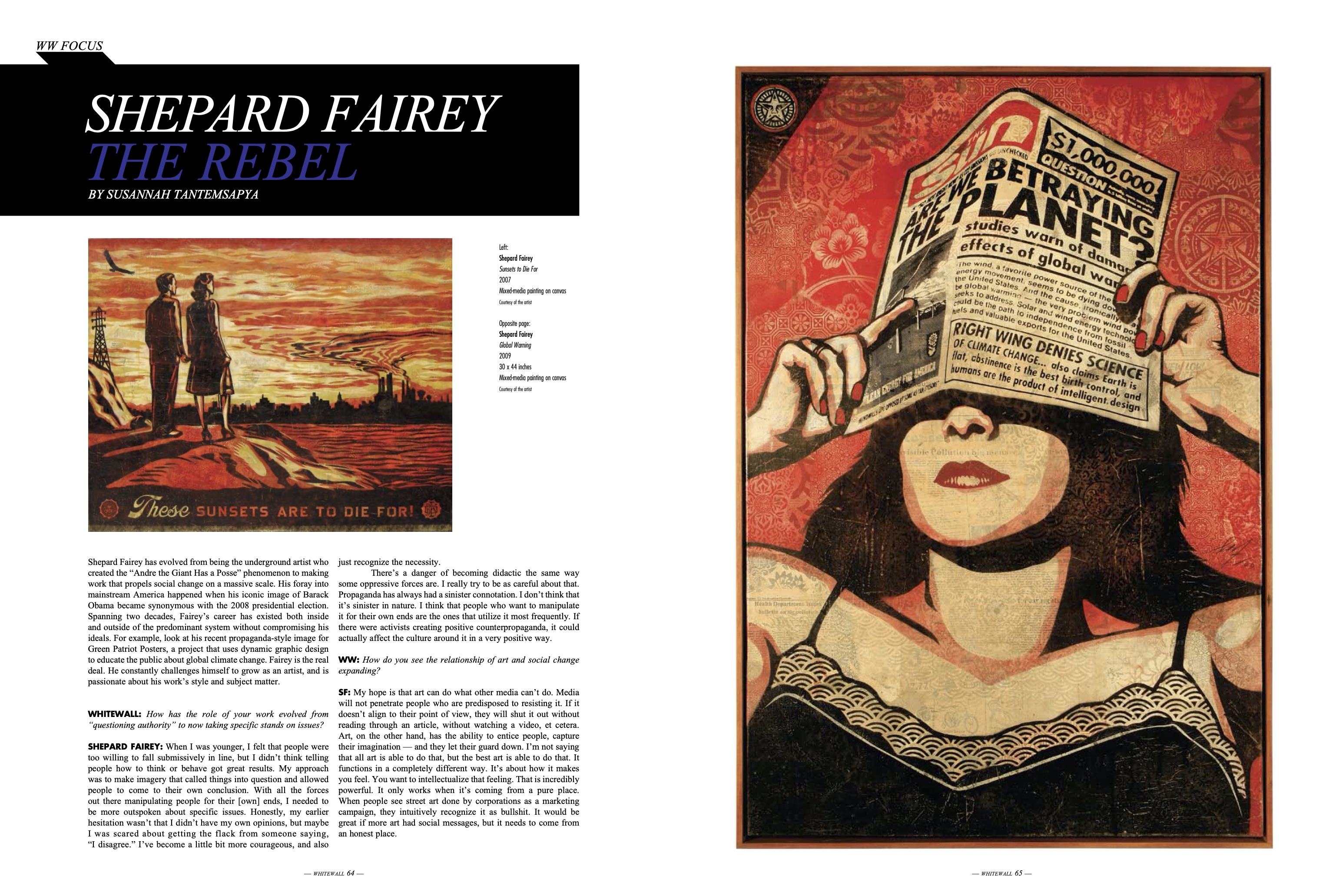

Shepard Fairey | Global Warming, 2009

30 x 44 inches | Mixed-media painting on canvas

Courtesy of artist

WW: You have mentioned that success in your career has allowed you the freedom to make art about social causes you’re passionate about. What projects are you working on now?

SF: I just made the 50th anniversary

poster for the Peace Corps to help

them raise funds. I think it’s a good

organization — my sister was in it,

and several of my friends have been

in it. The idea of public service in

another country gives perspective

on other cultures, economic

situations. And seeing how the U.S is perceived from the outside is very

valuable.

I’m doing images of Booker T. Washington, Maya Angelou, the Dalai Lama, Barack Obama, and Martin Luther King, Jr. for a public art project for the city of newark about peace and education. All those pieces are going to be painted at intersections around the city. It’s where the kind of art I’ve done as an outsider and that sense of urban renewal / civic pride converge. It’s not going to reinforce my “rebel brand” with 15-year-olds, but it’s actually a really awesome demonstration that you can’t put things in boxes. normally, I think cities have their heads up their asses, but this is an exciting project and will be really cool if it’s done right.

I’m doing images of Booker T. Washington, Maya Angelou, the Dalai Lama, Barack Obama, and Martin Luther King, Jr. for a public art project for the city of newark about peace and education. All those pieces are going to be painted at intersections around the city. It’s where the kind of art I’ve done as an outsider and that sense of urban renewal / civic pride converge. It’s not going to reinforce my “rebel brand” with 15-year-olds, but it’s actually a really awesome demonstration that you can’t put things in boxes. normally, I think cities have their heads up their asses, but this is an exciting project and will be really cool if it’s done right.

18 x 24 inches | Screenprint

Courtesy of artist

WW: Your iconic image of Barack Obama created a massive change from a grassroots level. do you hope that your collaboration for Feeding America could have that kind of lasting impact? What about other projects you are working on?

SF: Feeding America has been amazing because they rolled it out with a fairly large number of placements right away when I did it almost two years ago. They got such good feedback from the image. It’s of my daughter, Vivian. It won some sort of Ad Council thing, and this survey said that people were more likely to give money to the organization because it made them feel empathetic. The joke we have around here that that Vivian is pretty spoiled, and she’s holding up that bowl saying, “Can I pulease have some more sushi!” She’s [actually] not spoiled — we’re good parents — but relative to a starving kid she is.

WW: As you have mentioned before, we’re constantly bombarded with messaging. How have you responded to this ever-changing landscape as an artist, both in terms of your design and dissemination?

SF: With the volume of visual noise everywhere, I’m more aware than ever that an image or message needs to be very clear, powerful, and memorable. There’s no one visual formula to achieve that, but that’s got to be the objective.

WW: In your own words, what is design?

SF: Design is an organization of information that communicates

clearly and appealingly. There is art to a lot of design, but I

wouldn’t say that all design is art.

The distinction is that design uses

preexisting elements presented

in a very powerful, unique,

and memorable way, but isn’t

necessarily generating something from scratch.

WW: How do you see your work

evolving in the future?

SF: It’s always from just one

day to the next. Some days I feel

like the world is going in the

wrong direction; I’ve gotta make

some very in-your-face political

messages. Other days, I think I

should just make some stuff that’s

more soothing so people will calm

down and not shoot each other.

I never really know — I just do

what inspires me in the moment.

My dad always used to ask me what the five-year plan was. I don’t have a five-week plan.

My dad always used to ask me what the five-year plan was. I don’t have a five-week plan.

Something

that is important to me is making

things, as much as possible, that

are both timely and timeless. It

sounds contradictory. John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s “WAR IS OVeR! (If You Want It)” was very

timely for the Vietnam War, but it keeps being relevant, so it’s

timeless in a sense. When I really lived in the narrower world of

my punk / skateboard / street art subculture, issues that seemed

important to me at the time, now I look back and see that wasn’t

something great to invest energy in. now with age, I’m trying to

be smarter about how I apply myself. That’s loosely the strategy

moving forward. There are always going to be failures. Make

everything count as much as possible, and endure.

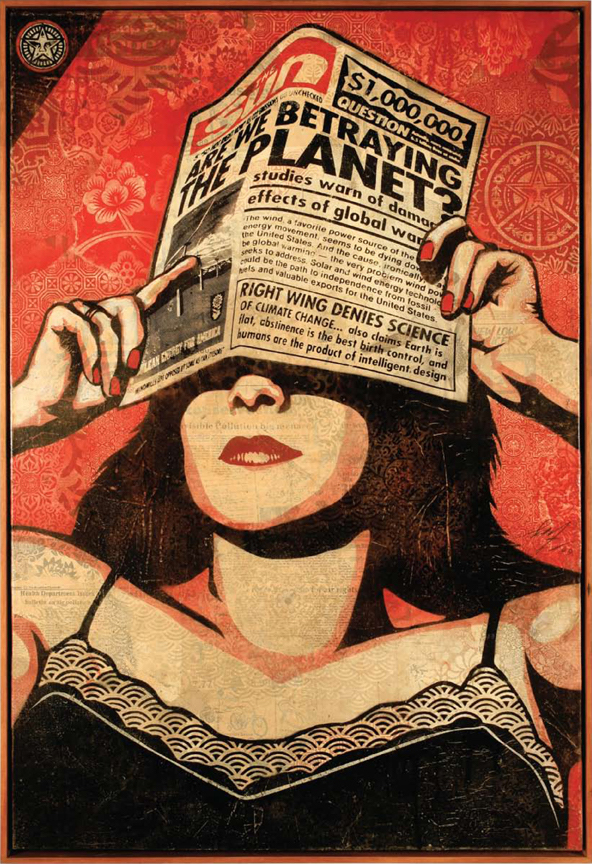

Left

Shepard Fairey | OBEY Soup Can

2005

Screen print 16 x 20 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Shepard Fairey | OBEY Soup Can

2005

Screen print 16 x 20 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Right

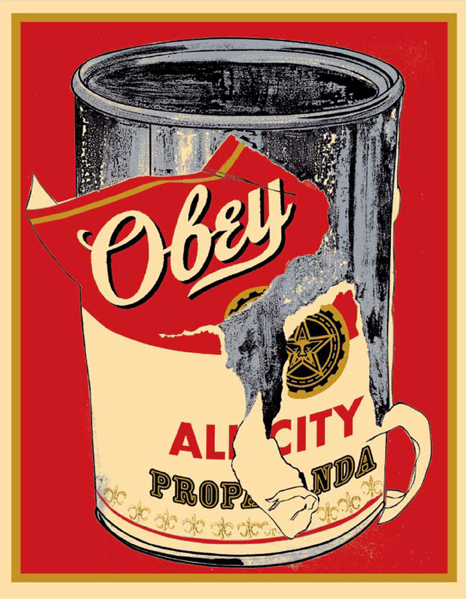

Shepard Fairey | Say Yes

2008

Screen print 18 x 24 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Shepard Fairey | Say Yes

2008

Screen print 18 x 24 inches

Courtesy of the artist

- Print -