Rashid Johnson’s

Island

October 2014

by Susannah Tantemsapya

Rashid Johnson’s Islands is the inaugural exhibition for the newly relocated David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles. This is the artist’s third solo show at the gallery, sprawling throughout its two, large spaces.

![]()

Rashid Johnson. Plateaus. 2014

The first holds the site-specific, floor-based sculpture Plateaus (2014), which was a built days before the opening in September. Johnson welded together open steel cubes, which once erected, are filled with varied, accumulated objects that in his words “occupy” its skeletal structure. This garden-like “island” is layered with plants, ceramics, concrete, plastic, brass, burned wood, grow lamps, shea butter, CB radios, rugs, and books. Organized in repetitive stacks, several editions of Richard Wright’s novel Native Son, SELLOUT: The Politics of Racial Betrayal by Harvard Professor Randall Kennedy, and the “Big Book” of Alcoholics Anonymous, incite a growing dialogue with each circumference of Plateaus.

Steel, lacquered paint, plants, cement, ceramics, plastic, copper, burnt wood, neons, radio equipment, shea butter, books. 579.1 x 457.2 x 457.2 cm

Fondation Louis Vuitton Collection, Paris

Upon entering the second gallery, there’s a combination of wood and shea sculptures. The wood sculptures hang on the walls, adorned with objects such as books, vinyl, plants, black soap, CB radios and of course, blocks of shea butter. The shea sculptures in the middle of the room feel minimal and open, housed in mahogany and glass. In fact, the aroma of shea butter floats throughout the entire exhibition space, providing a visceral connection to time, space and identity.

Throughout his career, Johnson has reflected upon his own identity as an African-American male and his work is often associated as post-black art. The exhibition Islands travels through various historical and pop cultural references, allowing us a glimpse through his own perspective, but also providing a feeling of nostalgia. Although the gallery itself is quite large, there is a welcoming presence, one of being at home in this constructed world that Johnson created.

Throughout his career, Johnson has reflected upon his own identity as an African-American male and his work is often associated as post-black art. The exhibition Islands travels through various historical and pop cultural references, allowing us a glimpse through his own perspective, but also providing a feeling of nostalgia. Although the gallery itself is quite large, there is a welcoming presence, one of being at home in this constructed world that Johnson created.

Rashid Johnson

Photo: Kendall Mills

Allora & Calzadilla

September 2014

by Susannah Tantemsapya

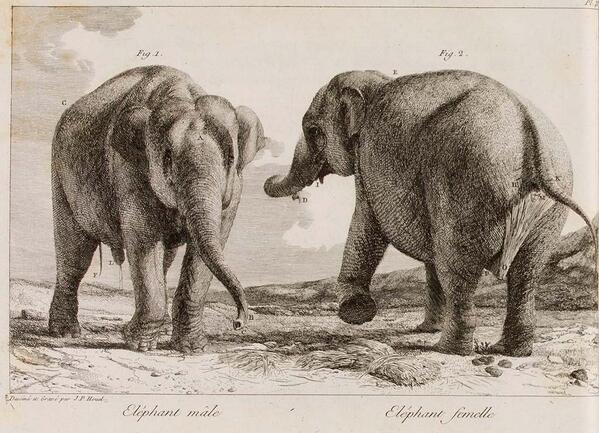

Allora & Calzadilla have been collaborating since 1995, partners in both work and life. For their first presentation in Los Angeles, they expanded upon their video work Apotomē (2013) with a newly commissioned performance this summer investigating biosemiotics and biomusicology at REDCAT. Their inspiration was a concert given to two elephants, Hans and Parkie, at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris in 1798. Whitewall spoke to this duo about how interspecies communication, music and the French Revolution tie into Apotomē.

Whitewall: When did you first discover Hans and Parkie? How did Apotomē take shape?

Jennifer Allora: For a couple of years now, we’ve been asked to make a project for the Autumn Festival, which happens in Paris annually. It’s more known for theatre and dance commissions, opera pieces and so on. They also have, in recent years, a contemporary art section. The city of Paris links up artists to different institutions. We had been looking around different sites such as the catacombs and the Museum of Man, which we have always really been interested in. In fact, another film project that we made was involved with the Museum of Man’s collections. One of the possible sites was the Natural History Museum of Paris, the Jardin des Plantes and that whole complex, which is kind the equivalent to the Smithsonian in the United States although it’s even older. We had gone on an initial visit there. It’s the first natural history museum: the paleontology and mineralogy departments, all these first collections were founded on this site that, of course, formally belonged to the King of France until the French Revolution.

Then it became public. One of the directors of the museum had taken us around to the menagerie; it’s the first zoo that was ever created in the world. We walked past the elephant pavilion and she told us the story of Hans and Parkie. It just captured our imagination. We had just left the Axolotl room. There’s a short story by Julio Cortázar about this guy who is obsessed with this Axolotl, which is in this other famous room in the menagerie. He keeps looking at the animal and looking at it until finally at the end of the story he becomes the animal. There’s this really great confusion between man and his identification with this nonhuman species. This kind of idea was inspired by the Cortázar story, and somehow our own interest in music. We had done a lot of work ourselves about what is the relationship between music and human evolution. We had just done a film about this discovery of a bone flute in Germany. We were thinking about those questions.

Guillermo Calzadilla: At that time, the relation between human and nonhuman life was also in the context of the French Revolution, meaning people who have rights and people who have no rights. The ones who have no rights are not treated like humans; they are treated like animals.

JA: Of course, this menagerie at the time had humans displayed like animals. This whole question was really pertinent…

GC: Human, nonhuman, life forms, abnormalities, and forms of oppression, slavery, all of this was the backdrop to this concert that was given to the elephants. So you had a really incredible combination of subjects that we have been exploring in our own work for over a decade. Then, that was one moment. Another moment was that we were looking at all these different institutions and by accident, we came across the bones of the elephants without looking for them.

JA: Of course, this menagerie at the time had humans displayed like animals. This whole question was really pertinent…

GC: Human, nonhuman, life forms, abnormalities, and forms of oppression, slavery, all of this was the backdrop to this concert that was given to the elephants. So you had a really incredible combination of subjects that we have been exploring in our own work for over a decade. Then, that was one moment. Another moment was that we were looking at all these different institutions and by accident, we came across the bones of the elephants without looking for them.

WW: After you already knew about the concert?

GC: We knew about the concert. Eventually we see these bones, and we ask, “What are these bones?” And they say, “Oh, these are the elephants Hans and Parkie.” Then we asked, “These are the same the elephants that we were told the story of this concert that was played to them?” And they said, “Yes, those are the same elephant remains.”

WW: So the elephants were alive when the concert was played? And they were part of the menagerie?

JA: Yes. Exactly.

GC: We knew about the concert. Eventually we see these bones, and we ask, “What are these bones?” And they say, “Oh, these are the elephants Hans and Parkie.” Then we asked, “These are the same the elephants that we were told the story of this concert that was played to them?” And they said, “Yes, those are the same elephant remains.”

WW: So the elephants were alive when the concert was played? And they were part of the menagerie?

JA: Yes. Exactly.

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, "Apotomē," 2013. Super 16 mm film transferred to HD, sound, 23:05 min.

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, "Apotomē," 2013. Super 16 mm film transferred to HD, sound, 23:05 min.

WW: Why did they create a concert for the elephants?

JA: That’s a very curious subject. It’s one of the only experiments documented of its kind where there was this attempt to try to have an interspecies communication. Music could be a vehicle to enter into the mind space of another species. That was the idea. There is no way for them to scientifically document or quantify that, so it was never repeated. It never became a model for future types of investigation. This, of course, is the moment when these scientific areas of study were first establishing and creating the norms of what is science, how you go about developing a relationship to scientific objects of study. But instead, we have what has been (established as) historical fact. Now we have the way we see the world today, which now is being challenged. There are new kinds of theory that are trying to reconsider those early hierarchies.

How are humans really separate from animals? What is the nature of our own constitution, what makes us separate or not? This idea of separateness is something that could be contested and challenged. This, obviously, didn’t prove to be amenable to those forms of analysis. If that path had continued, maybe 200 years later we would have a different understanding of a lot of these questions that we are still facing today about these categories of knowledge and the separations that we now take as a norm. Our contemporary feeling of separateness from other species, our hierarchy that we have developed as a result of natural history maybe would have changed at the very beginning if some of these other lines of inquiry had taken hold and maybe formed part of the social imagination.

GC: So the concert was made to see if human music may elicit some kind of reaction in nonhuman forms of life, in this case, the elephants. It was organized by musicians, not by scientists. It was a really strange event, almost capricious, illogical without any scientific foundation.

JA: In fact, there was a librarian that was part of the complex that documented some of the results. When "Ça ira" was played in a higher key, it excited Marguerite (an alternative name for Parkie), but Hans was not really interested. There was another piece that did get him finally sort of awoken. Then, of course, there are some many factors of the concert itself that one didn’t know how to quantify. Perhaps he reacted because he noticed the musicians were looking at him. We don’t know why.

GC: Or motion. That’s why it never became a scientific study.

WW: Because it wasn’t controlled enough.

GC: They could not quantify that question: can music effect animals? It became this isolated event during the backdrop of the French Revolution. It captured our attention and our imagination. Later when we discovered the bones of the same elephants, today in the present, we were completely amazed.

JA: Of course, those would be there. Cuvier, who studied comparative anatomy, was the one of the first people to do dissections. He dissected Hans and Parkie. He did some of the first experiments of dissection and understanding the anatomy of these large animals. He was, sort of, the founder of that field. That elephant was one of the first big animals to be dissected, studied and noted of its anatomy. And then the bones ended up in the Zooteque storage facility.

JA: Of course, those would be there. Cuvier, who studied comparative anatomy, was the one of the first people to do dissections. He dissected Hans and Parkie. He did some of the first experiments of dissection and understanding the anatomy of these large animals. He was, sort of, the founder of that field. That elephant was one of the first big animals to be dissected, studied and noted of its anatomy. And then the bones ended up in the Zooteque storage facility.

WW: The music that you chose for the video and the performance, was that based on the original concert?

GC: It’s exactly the same concert, the same songs in the same order.

JA: In the film, it’s not the same order because the actual concert would have lasted an hour and a half. This is a shortened version of it, fragments from it.

GC: Also the concert had parts that were instrumental; there were only a few parts that were singing. In completely different research, we had done works with the voice, voice displacement, the life of voices, and on and on. We found our about Tim Storms, the protagonist in the film that has this biological deformity, or characteristic or gift, however you want to see it. His (vocal chords) are basically twice as long as normal vocal cords and move five times faster. He can produce subsonic sounds that animals as large as elephants can hear.

JA: But humans cannot, outside of the audible human range.

GC: That point of understanding the characteristic of his particular voice and connecting what he could produce in terms of sound, and how even though it is coming from a human being, he actually can produce sounds that we, as human beings, cannot hear. Not even himself, he can only feel. However, animals as large as elephants can hear those sounds, so that became the structure or the link. Then, we invited him to come to Paris to sing the same songs walking through the Zooteque.

JA: We recorded it with an earthquake microphone because it’s very sensitive to low frequencies.

GC:

The structure was for him to sing the same concert to the bone remains.

WW: So they got it twice.

GC: They got it twice, exactly (laughs). But once now that they’re not there. It’s all about absence.

WW: How does everything tie in together?

GC: There is a relationship between Apotomē, the title of the film, which basically means when something has been cut off, the remainder of something, the leftover. And then, in this case, the remainder or leftover is the subsonic sound, something that we could not hear, but feel, but also the structure of the original concert. There is the voice, but the orchestra is not present. For the performance at REDCAT, there’s an orchestra, without singing, without vocals. So the orchestra is going to play the entire concert in the same order. There is a crossover of temporalities of leftover pieces. This is an experiment; we’ve never done it before. It should be interesting to see the way the two things inform each other and complement each other.

Mike Kelley’s Mobile Homestead

at MOCA in Los Angeles

July 2014

by Susannah Tantemsapya

As the Museum of Contemporary Art’s MIKE KELLEY retrospective draws to a close, so does the two-month residency of one of his most interactive works, Mobile Homestead. This community space and art gallery is a detachable façade on wheels; part of a full-scale replica of his suburban, childhood home that is permanently installed at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD).

This is Kelley’s “most sustained and largest piece of public art…taking the private space into the public space,” remarked MOCA retrospective curator Bennett Simpson. It investigates the notion of public art for Detroit: “a public artwork for a city with no public.”

This is Kelley’s “most sustained and largest piece of public art…taking the private space into the public space,” remarked MOCA retrospective curator Bennett Simpson. It investigates the notion of public art for Detroit: “a public artwork for a city with no public.”

Mike Kelley, Mobile Homestead Rolls Into Los Angeles

Mike Kelley, Mobile Homestead Rolls Into Los Angeles

Photo © Aleks Kocev/BFAnyc.com

For the first time outside of the Motor City, Mobile Homestead literally rolled to Los Angeles along the highways of America (not without a few flat tires). It sits perched beneath the Frank Gehry canopy outside to the Geffen Contemporary, acting as a hub for social services, art and educational initiatives through July 28.

MOCA’s programming integrated several local organizations to provide “public service activations” - upcoming events include:

July 26

Local United Network in Combating Hunger (L.U.N.C.H.) workshop to make several hundred bag lunches (each cost under a dollar) to be donated to Union Rescue Mission the following morning.

July 27/28

Our Skid Row Interactive Design Workshops on how to transform this area by looking at housing, public spaces, creative spaces, services, food access, health/sanitation, public safety, recreation, etc

Our Skid Row Interactive Design Workshops on how to transform this area by looking at housing, public spaces, creative spaces, services, food access, health/sanitation, public safety, recreation, etc

“Mobile Homestead is about the suburbanization of life. It was designed for social service and justice initiatives to upend the notion of a private, safe withdrawal,” said John Malpede, Founding Artistic Director of Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD).

Mike Kelley, production still, “The Mobile Homestead in front of the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan,” 2010. (Corine Vermuelen / Courtesy of Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts © Estate of Mike Kelley)

Mike Kelley, production still, “The Mobile Homestead in front of the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan,” 2010. (Corine Vermuelen / Courtesy of Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts © Estate of Mike Kelley)

This performance collective (formed in 1985) welcomed Mobile Homestead to Los Angeles during their WALK THE TALK parade through Skid Row in May. LAPD also installed a visual timeline of Skid Row, previously at the Queens Museum, during the first month of the residency: “Our installation is about the history of Skid Row: documentation of the vitality of this longstanding community, how it was developed by the people living and working there. This community has grown organically over a period of time, and is sometimes misrepresented by others. This is an attempt to remedy that. The attraction of urban life is that it is challenging, diverse and complex,” denotes Malpede.

Kelley also proved himself to be a compelling documentarian, creating two films about present-day Detroit seen through the POV of Mobile Homestead as it moved through its thoroughfares to the suburbs where he grew up: Going West on Michigan Ave from Downtown Detroit to Westland and Going East on Michigan Ave from Westland to Downtown Detroit. Kelley captured a comprehensive portrait of his hometown with the kind of intimacy only known from being part of a community itself. The films are installed within the retrospective along with a recent, special screening at Art Center College of Design.

Kelley also proved himself to be a compelling documentarian, creating two films about present-day Detroit seen through the POV of Mobile Homestead as it moved through its thoroughfares to the suburbs where he grew up: Going West on Michigan Ave from Downtown Detroit to Westland and Going East on Michigan Ave from Westland to Downtown Detroit. Kelley captured a comprehensive portrait of his hometown with the kind of intimacy only known from being part of a community itself. The films are installed within the retrospective along with a recent, special screening at Art Center College of Design.

The Mobile Homestead in front of the original Kelly home on Palmer Road in Westland, Michigan, 2010, Photo: MOCAD

Perhaps its Kelly’s own words that are most apropos to this ever-burgeoning project: “Mobile Homestead covertly makes a distinction between public art and private art, between the notions that art functions for the social good, and that art addresses personal desires and concerns…It has a public side, and a secret side.”

Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts offers free admission to the Mike Kelley retrospective every Saturday night in July through its closing party co-hosted with Opening Ceremony on July 26.

Kehinde Wiley

July 2014

by Susannah Tantemsapya

Last week, Kehinde Wiley unveiled his third and final installment for the Modern-Day Kings of Culture series featuring New York Knicks star Carmelo Anthony. Inspired by 18th and 19th century French portraiture, the artist collaborated with GREY GOOSE vodka to select cultural and thought leaders in sports, film (Spike Lee) and music (Swiss Beatz).

The setting was a reception and intimate dinner at the Sunset Tower Hotel in Los Angeles as a prelude to the ESPY awards. GREY GOOSE launched its new vodka, Le Melon The Fruit of Kings, extracted from the coveted Cavaillon melon grown in Provence, France. Legend has it that Kings would trade gold to have exclusive rights to this succulent fruit. Paul Cézanne illustrated the Cavaillon melon in an early, and at the time quite radical, still-life painting. In 1864, Alexander Dumas donated all 194 of his published (and future) works to the town of Cavaillon in order to receive an annuity of 12 melons every summer until his death in 1870.

Maître de Chai François Thibault developed this new recipe along with specialty cocktails served throughout the evening; these included his signature MELON MULE (think Cavaillon melon meets Moscow Mule) and LE MELON SCORE (GREY GOOSE Le Melon, MARTINI Bianco, fresh pineapple juice, club soda), dedicated to Anthony’s “extraordinary career on the court.”

Before dinner, Maximillian Chow, of Mr. Chow, moderated a conversation between Wiley and Anthony. Chow starts off by asking Anthony, “Did you (ever) think you would be a Muse for an artist?” and he replied, "Hell no!" The two-time Olympic Gold Medal winner and NBA player expressed how creativity helps him in sports to focus, that process "goes hand in hand" for him. Anthony likes to "dabble here and there…to see how tough it is to get into that creative mode in art."

Wiley then told Chow that this entire process was surreal because he's a huge fan of Anthony’s. The artist, who grew up in South Central Los Angeles and started attending art schools at age 11, doesn’t usually make commissions outside of the traditional art space. The idea of Modern-Day Kings of Culture plays with the notion of what a contemporary king is that he can truly relate to. "So much of my work is for people that don't have voices," states Wiley. The artist also passionately spoke to Whitewall earlier (over cocktails) about his new exhibition The World Stage: Haiti opening on September 13 at Roberts & Tilton in Culver City.

In relating seemingly unconnected worlds, Chow pointed out that sport is a “metaphor for war" for civilized humanity, "this not only is a graceful art form...but it's something we can feel proud of as a society."

In the sports press, there has been some poorly informed criticism towards Anthony, accusing him of commissioning the portrait for some narcissistic pleasure. In reality, the artwork will be auctioned off and the proceeds will go to a charity of his choice. "My importance for young kids is being a role model," said Anthony, “Family is what keeps me grounded…my son is who keeps me motivated.”

Wiley also discussed the public side of being an artist: “the foundational aspects of my creative self is being able to make a statement that you know won't satisfy everyone and then say ‘fuck it.’ You have the responsibility of saying something that you want to brace…a radical sense of honesty is core."

This was third event over the past several weeks to premiere Wiley’s iconic photographic portraits. Guests that night included Randy Jackson, L.A. Clipper Matt Barnes and wife Gloria Govan; USMNT international soccer player Jermaine Jones; singer Kelly Rowland and husband Tim Witherspoon; and Tina Knowles (mother of Beyoncé and Solange).

Eric Fischl

July 2014

by Susannah Tantemsapya

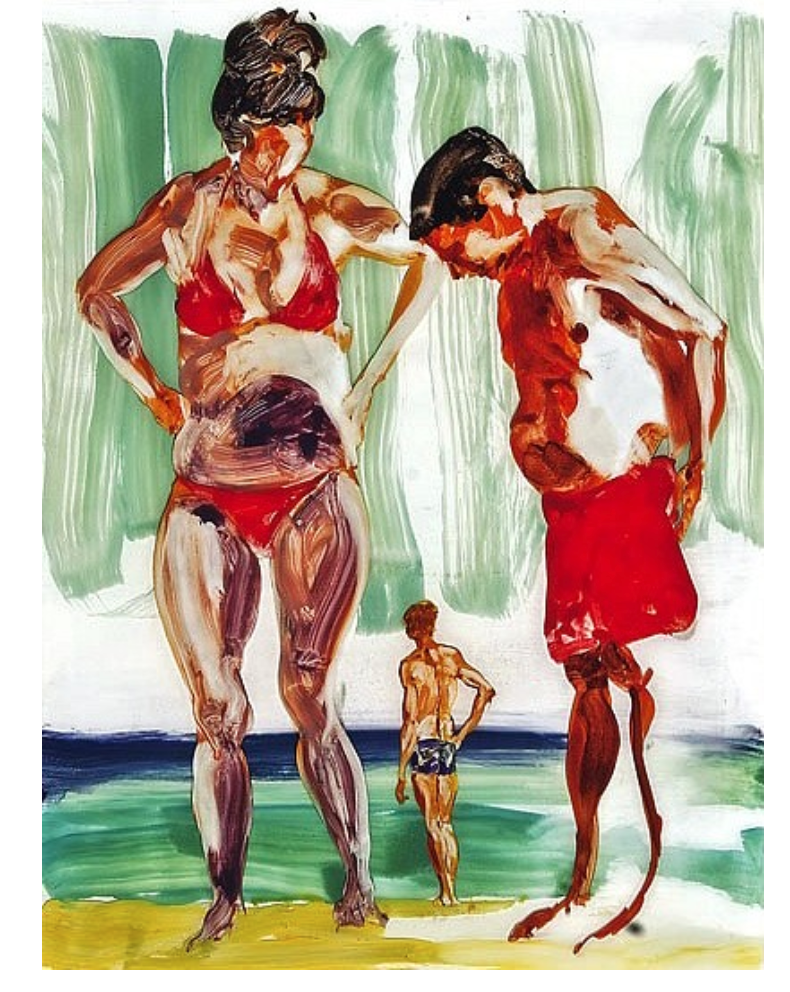

Eric Fischl, Tumbling Woman, Study, 2012

Glass, 12 x 18 x 14 in. Edition 2/10

FIS-002

Glass, 12 x 18 x 14 in. Edition 2/10

FIS-002

Sweet, sensitive and often a bit sad, the work of Eric Fischl intimately portrays not only the human figure, but also the emotional complexity of life. Currently, the artist has a solo exhibition at KM Fine Arts in Los Angeles. This selection of work is multidisciplinary: from watercolor beach tableaus (hand-painted collages with pigment inks and poured resin) to sculptures using bronze, cast glass, acrylic and steel. The oldest piece in the show dates back to 2004.

Part of the Neo-Expressionist movement in New York, Fischl first reached major prominence in 1980s. Dealer Mary Boone championed him along with contemporaries such as Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. By the 1990s though, his work had quickly fallen out of fashion. Since then, this artist has learned how to weather the capricious turns of the art world.

Depicting the mythology of American suburbia, the sexual nature of Fischl’s narrative paintings is wildly brushed out like a Cézanne still life. The complexity of his work is linked to his upbringing in Long Island. His mother’s addiction to alcohol led to her unpredictable and inappropriate behavior; she often walked around the house naked in front of Fischl and his brother.

The title of his recent memoir, BAD BOY: My Life On and Off the Canvas (written with Michael Stone), is taken from one of his early works, Bad Boy, 1981: a voyeuristic scene of a young boy shoving his hand in a purse while gazing at an older woman lying naked on a bed with her legs spread open, eyes shut.

In 1970, days before Fischl started Cal Arts on a full scholarship, his mother died from suicide by driving

her car into a tree.

“It was at that moment that my future was set. I vowed that I would never let the unspeakable also be unshowable. I would paint what could not be said,” explains Fischl in BAD BOY.

Hand-painted collage with pigment inks and poured resin,

60 x 80 in | Diptych: 60” x 40” each

FIS-015

Eric Fischl, Untitled, 2013

Hand-painted collage with pigment inks and poured resin, 40 x 30 in.

FIS - 004

Eric Fischl, Untitled, 2013

Hand-painted collage with pigment inks and poured resin, 40 x 30 in.

FIS - 004In conjunction with the opening at KM Fine Arts, there was a book signing as well as a talk hosted by the Broad Museum with polymath Steve Martin. Being friends for 25 years, their banter was educational, insightful and humorous. They discussed his time at Cal Arts when the school’s philosophy was anti-painting (only abstract painting was in vogue), yet Fischl continued to explore his humanity through the medium. “What you see in a painted portrait is a relationship” expressed Fischl on stage. Martin also shared a painting he owns of Fischl’s entitled Barbeque, which shows a kid blowing fire in front of his family poolside with a bowl of fish on a picnic table in the foreground. Fischl showed his newer paintings of art fair scenes, depicting the humor of that environment and of art in general. The artist also designed an annual banjo award out of bronze that Martin and his wife Anne Stringfield created.

Eric Fischl, Untitled, 2011

Watercolor, 60 x 40 in.

FIS-016

Watercolor, 60 x 40 in.

FIS-016

Eric Fischl, Untitled, 2013

Hand-painted collage with pigment inks and poured resin, 40 x 60 in.

FIS-014

Hand-painted collage with pigment inks and poured resin, 40 x 60 in.

FIS-014

Eric Fischl, Barbecue, 1982

Oil on canvas, 65 x 100 in.

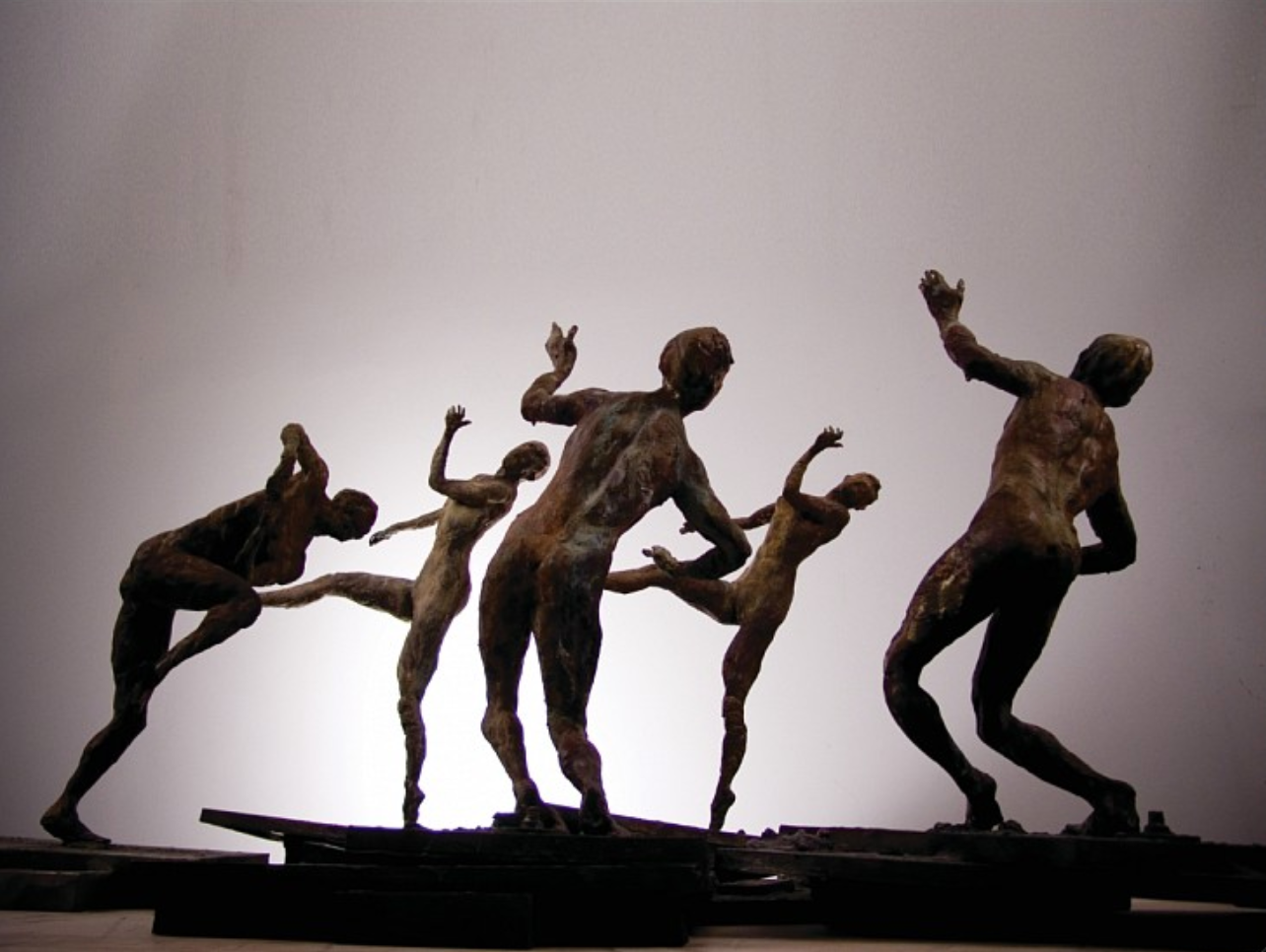

During the gallery’s opening reception, Fischl leaned on Ten Breaths: Congress of Wits Study, 2007 explaining how the “hand informs the eye” in creating a sculpture. He then encouraged those next to the work to touch it, to feel the weight and dimensions of the piece. Upon the entrance of the gallery, Tumbling Woman (Life Size), 2014 is situated in the front window looking out toward the street. His original rendition in 2002 was controversial since it commemorated September 11th. “America has an issue with the body,” as Fischl explains to Martin that the loss of the Twin Towers was the primary focus of this historic tragedy. “We didn’t know how to grieve or mourn the loss of human life, so we turned to architecture. There was no way to understand…the suffering of the body.” He also elaborated that in such a trauma, communities didn’t turn to their artists. Martin replied, “Art has different response times…the time it takes to (actually) settle in.”

Eric Fischl, Ten Breaths: Congress of Wits Study, 2007

Bronze | 27 x 40 x 68 in. | FIS - 009

Eric Fischl (b. 1948) has established himself among the most respected and relevant figurative artists working today. His paintings, sculptures, and works on paper have been shown widely across the U.S. and are featured in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. The exhibition, Eric Fischl, is on view through August 24, 2014 at KM Fine Arts Los Angeles.

Hans and Parkie Drawing

Hans and Parkie Drawing